Table of Contents

Snetzler Chamber Organ, 1761

The first organ at St. James’ Church was a 1761 Snetzler chamber organ which Bard family tradition states was given by Dr. Samuel Bard, future founder of St. James’, to his daughter Susan in the 1780s when the family still resided full time in New York City. Chamber organs, built to resemble fine furniture, were meant to be used in the home, with the unintended result being that these organs had a better record of survival from this time period than church organs. Such was the case with the Bard Snetzler, which still exists to this day in the Smithsonian. However, no verifiable documentation exists on the early history of this rare instrument, and we are essentially left with a couple of possible scenarios on when the Snetzler came into this country, and when it came into the Bard family.

The first organ at St. James’ Church was a 1761 Snetzler chamber organ which Bard family tradition states was given by Dr. Samuel Bard, future founder of St. James’, to his daughter Susan in the 1780s when the family still resided full time in New York City. Chamber organs, built to resemble fine furniture, were meant to be used in the home, with the unintended result being that these organs had a better record of survival from this time period than church organs. Such was the case with the Bard Snetzler, which still exists to this day in the Smithsonian. However, no verifiable documentation exists on the early history of this rare instrument, and we are essentially left with a couple of possible scenarios on when the Snetzler came into this country, and when it came into the Bard family.

The tradition is that it was imported from England before the Revolution, possibly by Samuel Bard himself. In 1902 the organ, still in the Bard family, was exhibited at the “Historical Musical Exhibition,” sponsored by Chickering and Sons in Horticultural Hall, Boston. The exhibition catalogue says the following about the piece, which it calls “An interesting specimen”: “[Item]1027: It was brought to this country before the Revolution and stored in a building in South Amboy [New Jersey] until after the end of hostilities”. Largely on the basis of this information, the source of which is unknown but was possibly the Bard family, the organ has been touted as being one of only five known Snetzler organs to have been brought over to North America before the Revolution. An unsigned paper from the turn of the 20th century, thought to have been written by a descendant of Susan Bard’s and one-time owner of the organ, Mary M. Johnstone, states that it was given to Susan on the occasion of her twelfth birthday in 1784 and traces the history of the organ within the family from that point forward.

In 1930 Susan Bard’s great granddaughter, Euphemia Johnson, published a collection of family letters dating from 1781, calling it “From an Old Secretary”, which is now in the Bard College Library. In a May 14, 1787 letter from Dr. Bard to Susan, who was staying at her uncle’s in Burlington, New Jersey, he writes, “I have sold your Forte Piano so that now you will have no instrument until your new one arrives from England.” If Susan was to have “no instrument” after the sale of her fortepiano, and she had been given the Snetzler organ three years previously, we are left to wonder about the organ’s whereabouts during this time. Euphemia Johnson surmises in a footnote to the 1787 letter: “Could this instrument [i.e. the one coming from England] be the pipe organ — one of the first in this country that Susan bequeathed to her eldest daughter and which was used in the first St. James Church…”. It would appear that Euphemia Johnson was unaware of any family tradition that the organ had been imported much earlier and given to Susan in 1784. The fact that the new instrument was coming from England provides no clue as to what it was, either: there were few if any American manufacturers of fortepianos at that time, so it could very well have been another fortepiano, perhaps the latest model.

Susan Bard was evidently an accomplished musician and singer. In a 1788 letter from her aunt, Susan is told, “Mr. McBlead tells me that you play better than any person he has heard in the Northland. Continue your excellent application and you may even excell (sic) Miss Eccles.” (Miss Eccles was a noted harpsichordist of the day). In another letter from Dr. Bard to Susan, dated August 25, 1789, he encourages her “playing and singing”. At the time of its writing, President Washington was recuperating from an emergency operation on a carbuncle of the thigh, performed by Dr. Bard and his father, Dr. John Bard, which is credited with saving the President’s life. In the letter, Susan is instructed by her father, “among the productions complimentary to the President, I wish you would select the most delicate and best set, and make yourself mistress of it, as he is my patron as well as my patient. I should choose to hear you sing his praises, the more particularly as his virtue and merit set flattery at defiance.” It has been speculated that Susan Bard played the Snetztler organ for the President, if she had the occasion to play for him at all. However, in none of the family letters in the Bard collection is Susan mentioned as playing an organ, while her playing a “forte piano” or “piano forte” (the two terms used interchangeably) is noted several times. It is conceivable that for some reason she never did master the Snetzler.

The Bards relocated permanently to Hyde Park sometime in the early 1800s, Samuel Bard having inherited his father’s estate there, and family tradition states that Susan gave the organ to her daughter Mary E. Johnston (also spelled Johnstone, and not to be confused with the Mary M. Johnstone previously mentioned). In 1811 Samuel Bard founded St. James’ Church, and around 1815 Mary loaned the organ to St. James’ and began volunteering her services as the church’s first organist, a position she held for about 20 years. The organ presumably remained in the church during that entire time. However, in describing this church in his 1913 “Historical Notes of St. James Parish”, the Rev. Edward Newton says that “the west end organ loft, where was a small melodeon loaned by Miss Johnston, who herself volunteered to serve as organist, was reached by a stairway from the vestibule [narthex] to the tower.” A melodeon was an American-made reed organ, not a pipe organ, and very different in appearance from the Snetzler so it would have been difficult to confuse the two instruments. Also, melodeon organs came about later, their first known use being around 1844, the same year this first St. James’ Church was deemed structurally unstable and torn down. Another mystery, to be sure.

In 1844 the current church was built on the same location as the first church and the following year the Vestry voted unanimously that “the organ belonging to Miss Johnstone which has been so long used in the service of the church be put up and repaired for use at the expense of the Vestry.” Although not named, this organ was presumably the Snetzler. According to family records, however, the repaired organ was never reinstalled in the new church but was returned to the family at that time. In addition to the repairs that had been done, the decorative front pipes had been removed and replaced with a cloth screen, and the keyboard colors were reversed (originally having been black naturals and ivory sharps, as was typical of Snetzler organs). No reason has come down to us for this change.

In 1858 Mary Johnston moved to western New York and took the Snetzler organ with her, and from there it passed down through her family. In 1938 St. James’ Church had an opportunity to purchase the organ, but as the church had neither the funds nor the place to store it, the Vestry voted against doing so, a decision which has been regretted many times since. However, most churches are not in the position to be organ conservators, and the acquisition of the Snetzler by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D. C. in 1968 was probably in the instrument’s best interests. It has since been painstakingly restored, and is housed within the Smithsonian’s National Museum of History collection of rare musical instruments.

In the Smithsonian’s estimation, this organ is significant because John Snetzler was England’s premier organ builder of the 18th century, and also because of its association with Dr. Samuel Bard, considered a leading citizen of the Revolutionary period. This is also one of only a handful of Snetzler organs brought over to this country during the mid to late 1700s still in existence, and with its original pipes, wind-chest and bellows, mechanical action, and mahogany case.

The organ contains five voices: Stopped Diapason (8’), Open Diapason (8’, treble only, from cą), Flute (4’), Fifteenth (2’), and a divided Sesquialter (bass) – Cornet (treble) II. The compass is fifty-four Notes, GG to eł (lacking GG#, AA#, BB, C#).

Inside the Snetzler organ, the following quip is written in German under Snetzler’s signature but in a different hand:

Ein Leben wie in Paradeis haben wir’s auf dieser Weld.

Herr Adam un Frau Eva die hatten auch kein Geld.

This was deciphered and translated by Rodney Dennis, curator of manuscripts at the Houghton Library, and Eugene Weber, Associate Professor of German, Harvard University, as follows:

A life as in paradise have we on this earth.

Adam and Eve also had no money.

The In-Between Years

From the mid-1840s to 1885, no definitive information exists on the organs at St. James’ Parish, which as of 1856 also included a chapel on East Market Street. The first salaried organist was Elizabeth A. Drom, who was employed from 1859-1874 as the organist for both the church and the chapel, so we know there had to have been two organs beginning from around that time.

The Pipe Organ Database tells us that “a new, handsome, and sweet-toned organ at an expanse (sic) of $400” was installed at St. James’ in 1853, but the builder is not mentioned.

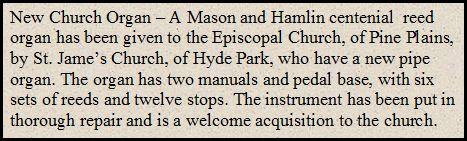

In May 1917 the following notice appeared in the Pine Plains Register, a newspaper in Pine Plains, Dutchess County, New York:

This Mason and Hamlin centennial organ, which as its name suggests was built to commemorate the country’s centennial in 1876, most likely came to St. James’ during the latter part of this “in-between” period.

In 1885 St. James’ donated an organ to the newly consecrated Mission Church of the Holy Cross in Clintondale, Ulster County, New York.

The Roosevelt Organ

In 1885, parishioner Walter Langdon, Jr., grandson of John Jacob Astor and a friend of the Roosevelt family, donated an organ to the church and another to the chapel in memory of his wife. He must have  had a fondness for organs or organ music, because in 1888 he also donated an Odell tracker pipe organ to the Reformed Dutch Church of Hyde Park.

had a fondness for organs or organ music, because in 1888 he also donated an Odell tracker pipe organ to the Reformed Dutch Church of Hyde Park.

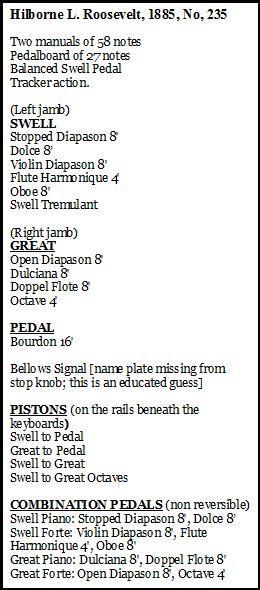

The two organs Langdon donated to St. James’ were the 234th and 235th organs to come out of the factory of Roosevelt Pipe Organ Builders, owned by brothers Hilborne and Frank Roosevelt, first cousins of Theodore Roosevelt. During their careers the Roosevelt brothers built some of the largest organs in the United States, which were prized for their quality and tone.

The two organs Langdon donated to St. James’ were the 234th and 235th organs to come out of the factory of Roosevelt Pipe Organ Builders, owned by brothers Hilborne and Frank Roosevelt, first cousins of Theodore Roosevelt. During their careers the Roosevelt brothers built some of the largest organs in the United States, which were prized for their quality and tone.

It would seem that one of these Roosevelt organs replaced the organ that St. James’ donated to the Clintondale church, since both events occurred in 1885. The other almost certainly replaced the Mason and Hamlin centennial organ which was donated later to the Pine Plains church, meaning the M&H organ could have sat in storage for those 32 years (however it is a bit of a mystery why the 1917 newspaper article refers to the organ replacing the Mason and Hamlin as new when it can only have been the Roosevelt organ installed in 1885).

The Roosevelt organ installed at the chapel in 1885 is there to this day, although it is not in working order. This instrument is considered important because of its rarity; its superb, unaltered condition; the fact that it is in its original position in the building for which it was commissioned, designed, built, voiced, and tonally finished; certain customizations that make it unique; and lastly the triple nameplate which reads “New York – Philadelphia – Baltimore”, which may be the only one of its kind from a Roosevelt organ still in existence. Hilborne Roosevelt most likely personally oversaw this organ’s construction in Manhattan, and perhaps had occasion to worship at St. James’ while the instrument was being finished.

There is a little room behind the organ where children, including Carolyn Van Wagner and John Golden’s father, were paid 10 cents an hour to pump the organ for chapel services before the organ was electrified.

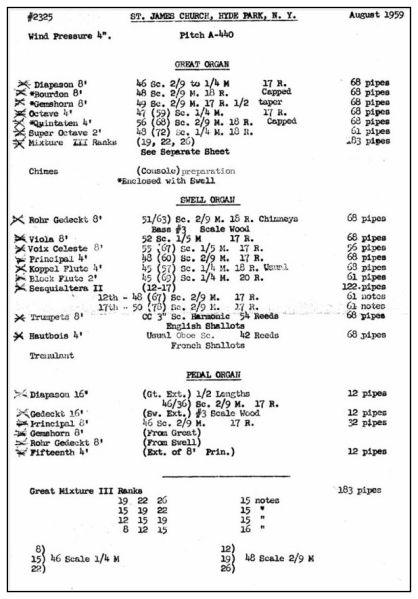

The Austin Organ - Opus 2325

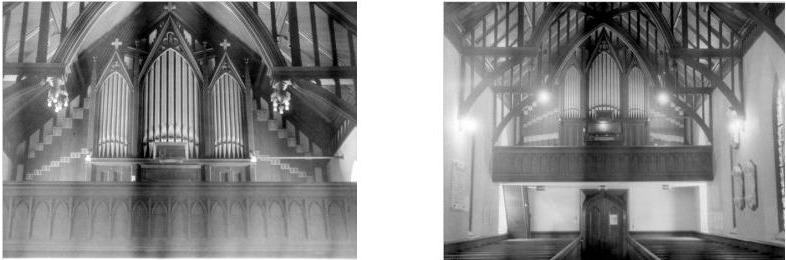

In 1960 after 75 years of faithful service, the Roosevelt organ at the church was dismantled and replaced with a pipe organ built by Austin Organ Company, Inc. with instructions to the organ builder that the antique Roosevelt organ case was to be “rescued”. Thus, the new display pipes of the Austin were fitted into the original casework. This allowed the church to modernize while maintaining the magnificent casework of the old instrument.

The Austin Organ Company is based in Hartford, Connecticut, and is one of the oldest continuously-operating organ manufacturers in the United States. They developed the Universal Air Chest System which was an airtight chamber with the chest action on top of the chamber. This meant that the chest could be entered while the organ was turned on, thus allowing for fine adjustments of the organ action.

The Austin Organ Company is based in Hartford, Connecticut, and is one of the oldest continuously-operating organ manufacturers in the United States. They developed the Universal Air Chest System which was an airtight chamber with the chest action on top of the chamber. This meant that the chest could be entered while the organ was turned on, thus allowing for fine adjustments of the organ action.

Sadly, the Austin organ and the 1885 Roosevelt case perished in the fire that gutted the church in 1984.

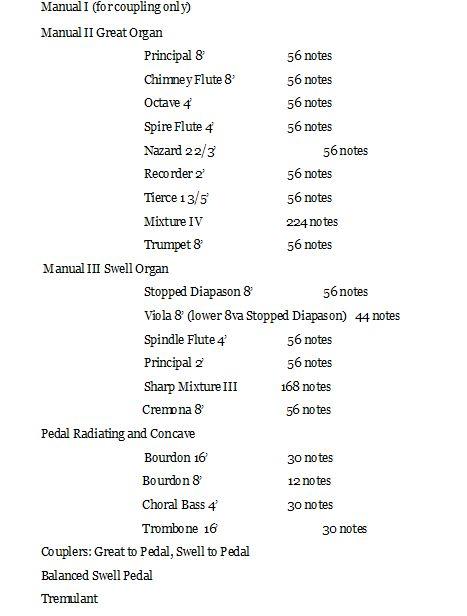

The Bozeman Organ - Opus 47

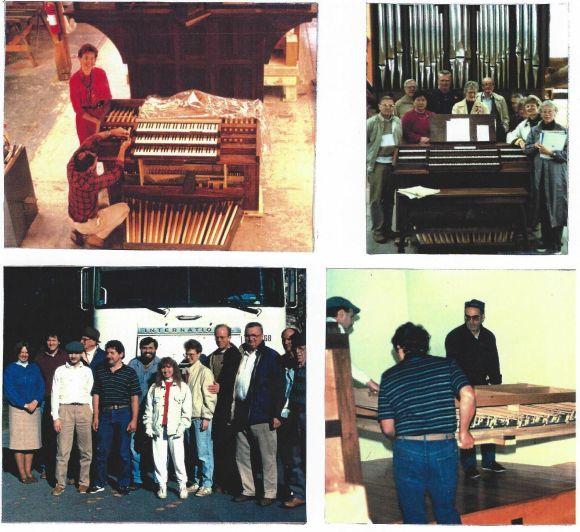

After the fire, a committee was formed to research and select a company to build and install the next organ. During this time, music was provided on a keyboard played by parishioner Gloria Golden. In 1988 the committee, chaired by George Buso with David Hurd, professor of church music and organist at the General Theological Seminary in New York City as consultant, decided upon a fully mechanical-action tracker pipe organ to be designed and built by George Bozeman of Deerfield, New Hampshire. Two years later, thousands of parts for the new organ were unloaded from the large moving van in front of the church. After weeks of work by the Bozeman staff, the congregation heard the Opus 47 for the first time on February 10, 1991. Members of the Bozeman Organ Company who worked on it signed their names on a plaque inside the organ.

After the fire, a committee was formed to research and select a company to build and install the next organ. During this time, music was provided on a keyboard played by parishioner Gloria Golden. In 1988 the committee, chaired by George Buso with David Hurd, professor of church music and organist at the General Theological Seminary in New York City as consultant, decided upon a fully mechanical-action tracker pipe organ to be designed and built by George Bozeman of Deerfield, New Hampshire. Two years later, thousands of parts for the new organ were unloaded from the large moving van in front of the church. After weeks of work by the Bozeman staff, the congregation heard the Opus 47 for the first time on February 10, 1991. Members of the Bozeman Organ Company who worked on it signed their names on a plaque inside the organ.

In the Opus 47, everything is mechanical except for the blower that keeps the door-sized set of bellows inflated. Unlike the feel of an electric pipe organ, the organist can sense the pipes open when pressing a key. As George Bozeman has said, “In mechanical terms, I don’t think there’s anything here that someone from the 1850s, 1750s, and even 1650s would be astounded at.” The casework is of solid black walnut to harmonize with the interior of the church.

Sources

Catalogue of the Exhibition, Horticultural Hall, Boston, January 11 to 26, 1902, page 52, published 1902 by The Barta Press, Boston.

“A Snetzler Chamber Organ of 1761” by John T. Fesperman, published by Smithsonian Institution Press, 1970.

“From an Old Secretary, Being Selections from the Correspondence and Diaries of Susan Bard Johnston”, edited by Euphemia Johnson, in the Bard Family Papers, Bard College Library.

“Historical notes of Saint James Parish, Hyde Park-on-Hudson” by Edward Pearson Newton, published by the A.V. Haight Co., Poughkeepsie, New York, 1913.

Information on the Roosevelt organs is taken in part from a report by the artistic and tonal director of Glück Pipe Organs, Sebastian Matthäus Glück.

American Guild of Organists – Specification on the Roosevelt organ prepared by Joseph Bertolozzi, renowned composer and organist, May, 2007.